MAY 3, 2019

"Poverty leaves a mark on our genes"

At nearly 50,000 deaths each year, the opioid epidemic is shaping up to be the central public health issue of the 2020 presidential election. From President Trump on the right with a declaration of national emergency to Sen. Elizabeth Warren on the left with a 10-year, $100 billion plan to fight addiction, the candidates are racing to outdo each other on one of the few issues that transcends our polarized politics.

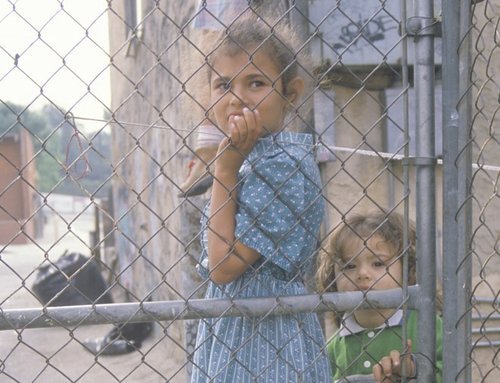

But there’s another burgeoning public health crisis that few of the candidates are talking about. Its victims are numbered not in the thousands but in the millions. And it primarily affects kids, putting them at serious risk for heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and more.

I’m talking about toxic stress, a condition that affects as many as 34 million kids in the U.S., and that can be identified by a simple pediatric screening.

Never heard of toxic stress? You aren’t alone: Most Americans haven’t either. And only a handful of candidates and elected officials have addressed the issue. Yet it should be at the top of the health debate.

Toxic stress isn’t caused by a virus or bacteria or a drug. Instead, it’s what happens when children experience very traumatic events such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a home with a violent or seriously ill parent. Toxic stress can cause long-term health issues starting in childhood, increasing the risk for chronic conditions and poor health by two to four times.

The significant risks of toxic stress were “discovered” in a seminal 1998 study by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It found that adults who were repeatedly exposed to abuse and other severe trauma or stressors as children – which the researchers called adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs — were more likely to develop alcoholism, drug addiction, severe obesity, depression, and other health issues. The more ACEs individuals had, the higher their risk for many of the leading causes of death in the United States, including heart disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, and cancer.

We now know that when kids experience severe trauma or stress, their fight-or-flight response button gets stuck on “high,” continuously pumping stress hormones into the bloodstream. In developing brains and bodies, this can weaken the immune system, disrupt hormone balances, influence brain development, and even alter DNA. It can also reduce life expectancy by 20 years for those with six or more adverse childhood experiences.

The science linking ACEs to poor health and behavioral outcomes is abundant. So it is imperative that we identify children at risk for toxic stress and get them screened through a simple, low-cost process. Using a questionnaire, pediatricians can easily ask parents about their child’s exposure to adverse experiences; teens may be able to fill out their own questionnaire. In addition to the original 10 adverse childhood experiences in the Kaiser-CDC study, leading screening tools now include questions about gun violence, family separation, discrimination, bullying, and food or housing insecurity.

Armed with screening results, pediatricians can educate parents and give them greater guidance, support, and resources to protect their child’s brain and body. Doing that could dramatically improve the health of millions, save billions in health care dollars, and prevent endless cycles of trauma within generations of families.

In California, where I live and work, lawmakers are so concerned about toxic stress and the threat it poses to their constituents that they passed Assembly Bill 340. It will provide universal screening for adverse childhood experiences for every child enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program — that’s 5.4 million children. Gov. Gavin Newsom built on this momentum and proposed nearly $105 million in the state budget for ACEs screening, provider training, and referrals for children and adults. While our immediate focus is on the need for screening and intervention, our long-term goal is to extend the debate beyond medical interventions to the structural and policy barriers that underlie adverse childhood experiences.

Given California’s leadership on this issue, it’s no surprise that Kamala Harris, a Democratic senator who represents the state and a candidate for president in the 2020 election, talked about the lifelong consequences of childhood trauma during her CNN Town Hall in April. Now we need Harris and other candidates to commit to action, such as requiring that all kids covered by Medicaid or other federal health programs get screened for toxic stress.

Like the opioid epidemic, toxic stress is a national crisis that requires a national solution. The work starts with screening and interventions. It ends when we understand the biology of injustice and the science of hope and resilience and apply that knowledge to those at risk. That’s why every presidential candidate should be talking about it and promising to act on it.

Jim Hickman heads the Center for Youth Wellness, a nonprofit organization based in the Bayview district of San Francisco, and is a member of the advisory committee for the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers’ National Center for Complex Health and Social Needs.

Image credit: At the Verner Center in Asheville, N.C., the "peace table" is designated to help kids work out conflicts with their classmates. CHUCK BURTON/AP.

Originally published on STAT: First Opinion on June 21, 2019